Tumour Testing vs Genetic Testing vs CGP

As we know, cancer is often caused by changes to the DNA known as mutations, which can be either acquired throughout a person’s lifetime (somatic mutations) or passed down through a family (germline mutations). We can perform various types of testing to identify which mutation(s) a person has in their DNA including tumour testing, genetic testing, and comprehensive genomic profiling.

Tumour Testing: Tumour testing involves obtaining a sample of a person’s DNA directly from their tumour to see what mutations are present in that cancerous region. While this does involve sequencing, a process using technology to figure out the exact order someone’s DNA is in, it does not confirm that a cancer is hereditary. Changes can occur in someone’s DNA after it has been passed down by their parents, which is why tumour testing is sometimes referred to as somatic testing.

Genetic Testing: When a health practitioner mentions genetic testing they are likely referencing tests that look for germline mutations in your DNA that were passed down from a parent. This test involves using testing technology to observe the order of your DNA on a sample coming from somewhere other than the tumour. This is because the mutations passed down from a person’s mom and dad will be found in every cell in the body, whereas mutations developed over the lifetime will only exist in a certain region (the tumour). Therefore, this type of test can inform someone with a family history of cancer of their own personal risk, before a tumour has even formed. Genetic tests vary; this term could refer to a test that checks for a single mutation in the DNA or multiple at the same time. Genetic testing is sometimes referred to as germline testing.

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP): This term refers to the process of testing for both somatic or germline mutations. The distinction with CGP is that this approach to testing always involves a wide range of genes in what we call a panel. It is often more efficient to get multiple answers at once by testing for multiple genes that are tied to multiple different types of cancer at once. Within a gene, CGP is able to detect four different classes of change; it can pick up on whether something in the DNA was deleted, rearranged, swapped and if a section was removed or replicated multiple times[1]. For instance, someone with a family history of breast cancer may want to test for Hereditary breast ovarian cancer syndrome; this panel could involve 19 genes including: ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, EPCAM, HOXB13, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PALB2, PMS2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, STK11, TP53[2]. The technology typically used to perform CGP is called Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS).

For more information defining these three types of testing, visit this link.

Utility

The information below is a summarized version of what was shared at the CCRAN Biomarkers Conference 2025

Generating a Cost-Benefit Analysis to Help Support Access to Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP) for Five Metastatic Cancers in Canada: Helping to Ensure CGP Becomes a Standard of Care in Canada!

Eddy Nason, MPhil, B.Sc., Director, Health, Conference Board of Canada ‘

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ks1nc8M-Tek

Identifying biomarkers with implications in cancer and therapeutics is critical because panels can have 350?500 genes in them, not all of which are useful in obtaining diagnostic information that can inform treatment. Further, biomarker relevance isn’t limited to one cancer type; treatments specific to a biomarker like BRCA could benefit patients with different cancer types such as breast, ovarian, prostate and pancreatic cancers. Given that the number of identified biomarkers and their discovered associations with various cancers is constantly growing, the Director of Health for the Conference Board of Canada highlighted the benefits of creating a biomarker database. To have a bank full of information, including a comprehensive list of cancer biomarkers, their locations within our DNA, the cancer types they are associated with, etc. would enable a more seamless transition from research to clinical applications.

Implementing CGP as Standard of Care

The information below is a summarized version of what was shared at the CCRAN Biomarkers Conference 2025

What Will it Take to Implement Comprehensive Genomic Profiling as a Standard of Care in Canada for the Management of Metastatic Disease in Cancer Patients?

Cassandra Macaulay, B.Sc., MHS, RTNM, Chief Research Officer, CCRAN

Laura Greer, Patient Expert; Senior Vice President and National Practice Lead, Health & Wellness, Burson Canada; Breast Cancer Advocate

Dr. Laura Weeks, Ph.D.?, Director, Health Technology Assessment, CDA

Don Husereau, B.Sc. Pharm, M.Sc., Adjunct Professor of Medicine, University of Ottawa

Dr. Monika Slovinec D’Angelo, Ph.D., Health System and Policy Consultant, Adjunct Professor, University of Ottawa

Dr. David Stewart, MD, FRCP(C), Medical Oncologist, The Ottawa Hospital – Cancer Centre; Professor of Medicine, University of Ottawa

Dr. David Cescon, MD, Ph.D., Medical Oncologist & Clinician Scientist, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre; Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto

Dr. Robert Bell, MDCM, M.Sc., FRCSC, FACS, FRCSE (Hon), Former Ontario Deputy Minister of Health; Professor Emeritus, Department of Surgery, University of Toronto

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_r_y3VALmMk

Canadian Drug Agency (CDA) Addressing Biomarker Testing in Oncology

Dr. Laura Weeks, Ph.D., Director, Health Technology Assessment, CDA

On behalf of Canada’s Drug Agency (CDA), Dr. Laura Weeks shared information about biomarker testing reimbursement and what is needed to prepare for new processes and broader implementation of CGP. Currently, the CDA provides recommendations for reimbursement of drug therapies, but does not have a similar process for diagnostic testing. Some of the challenges there include the fact that there are typically different funders and decision makers for drug vs biomarker requirements; the two systems aren’t coordinated, which limits timely access. At present, they are making an assessment framework based on recommendations from their advisory panel that will inform decisions about funding and adoption of cancer biomarker testing. The framework will also outline the criteria to consider when making these important decisions, and the process that should be in place to allow for timely assessments. This is intended to be a step in the right direction towards being able to evaluate CGP, and it is anticipated that it will be finalized in the fall, after incorporating changes highlighted during a summer feedback period.

The Impact of Regulatory Delays

Dr. David Stewart, MD, FRCP(C), Medical Oncologist, The Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre; Professor of Medicine, University of Ottawa

As to the impact of regulatory delays on clinical care, when it comes to the development of a new drug that improves life expectancy by a few months, there’s around 80,000 life years lost worldwide per year of delay in getting the drug approved. Beyond approval, there’s the concern of funding. Canada is way behind most OECD countries with respect to the funding of new drugs. In fact, we tend to lag two years behind the median OECD times, causing thousands of Canadian lives lost during that delay period. In the case of early-stage localized cancers, every week of delay leads to a 1% decrease in the probability of cure.

The reality is, if patients can’t access treatments fast enough, we use far more resources in trying to maintain their health long enough for them to receive the treatment which will actually help them.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

The information below is a continued summary of what was shared at the CCRAN 2025 Biomarker Conference

Generating a Cost-Benefit Analysis to Help Support Access to Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP) for Five Metastatic Cancers in Canada: Helping to Ensure CGP Becomes a Standard of Care in Canada!

Eddy Nason, MPhil, B.Sc., Director, Health, Conference Board of Canada

The factors that influence cost include panel size for genetic testing, sequential testing,in the case of lower success: redoing a biopsy and testing, treatment regimen and treatment delays which increase cost.

Cost of CGP

Please note that this information shared below is preliminary and subject to change.

The Conference of Canada calculated the cost of six years worth of patients with lung, breast, prostate, pancreas or colorectal cancer being tested to see if their cancer has spread using CGP. The costs were estimated to be $638,600,093.15 for FoundationOne tests, $136,607,314.12 for Oncomine Precision Assay, $174,999,713.16 for AmpliSeq and $499,642,002.14 for Oncomine Comprehensive Assay v3.

Table 1: Costs associated with CGP-NGS Testing over a 6 year period

| Cancer Type | FoundationOne | Oncomine Precision Assay | Ampliseq | Oncomine Comprehensive Assay v3 |

| Lung | $337,779,202.04 | $72,256,659.61 | $92,563,819.05 | $269,279,129.62 |

| Breast | $25,479,741.18 | $5,450,545.72 | $6,982,378.24 | $19,935,400.94 |

| Prostate | $56,446,854.53 | $12,074,932.76 | $15,468,496.57 | $44,164,132.94 |

| Pancreatic | $76,400,348.39 | $17,343,321.12 | $20,936,481.53 | $59,775,786.82 |

| Colorectal | $142,493,947.02 | $30,481,854.90 | $39,048,537.77 | $111,487,551.82 |

| Total | $638,600,093.15 | $136,607,314.12 | $174,999,713.16 | $499,642,002.14 |

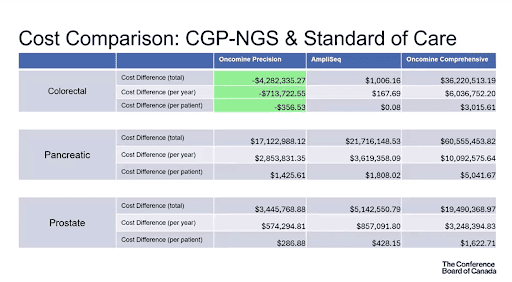

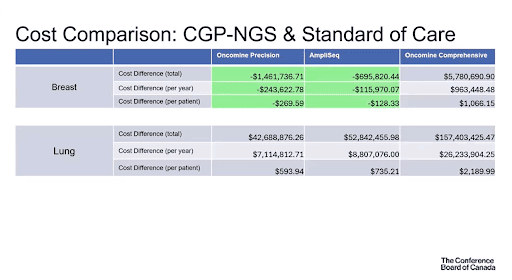

Cost comparison: CGP vs Standard of Care

A comparison of cost between CGP and current Standards of Care was done for total costs, cost per year and per patient, as depicted in the table below. Key findings included:

- Savings of $4,282,335.27 in total, $713,722.55 per year, and $356.53 per patient for colorectal cancer testing using Oncomine Precision

- Savings of $1,461,736.71 in total, $243,622.78 per year, and $269.59 per patient for breast cancer testing using Oncomine Precision

- Savings of $695,820.44 in total, $115,970.07 per year, and $128.33 per patient for breast cancer testing using Oncomine Precision

*The FoundationOne test was not included since it is not currently publicly funded

On the topic of funding, as of 2025, Genome Canada has committed to invest 200 million into precision medicine and genomic data for health. This will help promote a shift towards liquid biopsies for testing DNA, which are a less invasive option. They were on the CDA’s “2023 watchlist” as an emerging precision medicine approach.

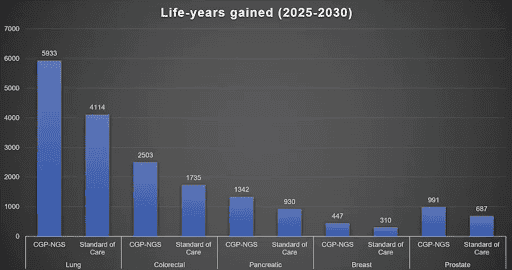

Benefits of CGP

One of the benefits of CGP was increased survival, estimated to be a total of 3440 life years gained across patients with lung, colorectal, pancreatic, breast and prostate cancer (see Life-years gained graph below). Another benefit was increased societal and economic contributions (see Increased Survival and Economic Contributions table below). Regardless of whether or not someone goes back to work, increased survival of one or more years contributes to $48,711+ to society/economy. The total economic contributions were estimated to be $180,736,741.95 across the 5 cancer types listed previously. Other benefits include increased clinical trial enrollment (+15% match) and eligibility (+5% increase), as well as indication of therapy options in other tumour types (76-80%).

With regard to panel size, larger size is beneficial in allowing for greater understanding of the tumour and identifying an increased number of targeted therapies or clinical trials to match patients to. On the flipside, it is more costly, leads to longer wait times for patients, requires increased resources (staff, time, etc.) and patients are limited by therapy availability (some may not be publicly funded).

As for implementing CGP as a Standard of Care, the benefits include the dozens of panels currently at Canadian oncology sites and an evolving public funding landscape for each province. We are also seeing some supplementary funding from researchers and industry to move this forward. However, increasing the panel size limits some of the usefulness in the Canadian setting; we don’t have the capacity to use all the findings that will come from CGP as not all biomarkers identified by testing have therapies targeting them yet. We must consider that biomarker and therapy matching success is not tumour specific and there would be a gap between the biomarker identification stage and treatment. Overcoming this gap would require an increase in medical pathologists.

| Cancer Type | Increased survival (LYG) | Economic Contributions ($) |

| Lung | 1820 | 95,595,569.65 |

| Breast | 137 | 7,214,759.97 |

| Prostate | 304 | 15,970,536.64 |

| Pancreatic | 412 | 21,626,768.37 |

| Colorectal | 768 | 40,329,107.33 |

| Total | 3440 | 180,736,741.95 |

Barriers & Benefits According to Patient Groups

CCRAN Biomarkers conference 2025

Reacting to the Findings of CCRAN’s Cost-Benefit Analysis Report: The Value of Accessing Comprehensive Genomic Profiling for Cancer Patients in Canada

Filomena Servidio-Italiano, Hon B.Sc., B.Ed., M.A., President & CEO, CCRAN

Jenn Gordon, Lead Strategic Operations and Engagement, Rethink Breast Cancer

Maureen Elliott, Senior Manager, Programs and Support, Pancreatic Cancer Canada

Bukun Adegbembo, M.Sc., Director of Operations, Canadian Breast Cancer Network

Stefanie Condon-Oldreive, Founder and Director, Craig’s Cause Pancreatic Cancer Society

Winky Yau, Manager, Medical Affairs, Lung Cancer Canada

Austin Zimmer, B.Sc., M.Sc., Support Services Manager & Research Coordinator, Prostate Cancer Foundation Canada

Current Barriers

- Time to receive the testing results

- Location: patients might have to go to the U.S. to get their testing done

- Incomplete biomarker testing: in Canada we have three biomarkers being tested for lung cancer whereas the U.S. tests nine

- Inconsistency across and within provinces: major urban centres have greater access to resources

These are critical to overcome since CGP determines the direction of treatment for the patient, who get to know the options available and make informed decisions; without knowledge you don’t have power. Beyond that, patients often feel as though they are racing against the clock to stay ahead of their disease, and CGP helps avoid that trial and error approach to treatment.

Benefits

- Allows for a more tailored treatment plan

- Reduced side effects

- Exposes patients to clinical trials

- Fewer emergency, hospital and doctor’s appointments

- Having the ability to plan ahead rather than having months left to live

- Patients are able to become engaged in their own lives again and the lives of their families

Key Takeaways

- Tumour types that currently show low benefit in cost analysis with CGP are unlikely to stay that way

- Research and clinical trial use of larger CGP panels leads to increased actionable mutations

- Learning health system approaches is key to realizing the potential of CGP data, even when mutations aren’t all actionable

- CGP opens doors to use of existing therapies for new tumour types

- Being able to bring therapies into use for multiple tumours increases their utility and potentially their cost-effectiveness

- Using CGP as a standard of care of the 5 cancers mentioned provides both current and future benefits

In summary, we currently have CGP in place for lung cancer as well as some breast and colorectal cancers, but want to expand our use of CGP in the clinical setting. The goal is for it to become the Standard of Care for breast, colorectal, pancreatic, prostate and lung cancer. In doing so, we could see up to 3440 life years gained and a $180 million economic benefit.

Role of the Genetic Counsellor

Genetic counsellors help educate patients as well as other healthcare workers on genetic medicine. Patients will see them before genetic testing to discuss their situation and family history in order to determine which test would be most appropriate. During an appointment you may notice them drawing out a tree made of circles and squares. This is a pedigree, it’s a genetic counsellor’s way of compiling someone’s family history into one place and can help to get a better picture of their potential for hereditary cancer. Before the existence of the field of genetics, patients were only treated once symptoms presented themselves. Clinicians are typically not as familiar with the process for individuals with a discovered risk factor (heritable gene) that do not yet have the disease, so this is where the skillset of a genetic counsellor comes into play. Following a genetic test, patients often see a genetic counsellor to discuss the results and next steps. Many genetic counsellors work alongside clinical geneticists and offer their services in person as well as virtually.

Some of the key skills of genetic counsellors include:

- Calculating genetic risk

- Explaining heredity in families

- Ordering genomic tests

- Interpreting genetic test results

- Predicting the risk of genetic disease

- Handling the psychosocial & ethical effects of testing

- Facilitating familial communication and coping

- Arranging tests for at-risk relatives

Mainstreaming

Genetic counsellors are in high demand and wait times to meet with one can be long. In response, the process of mainstreaming has become an alternate route to genetic testing where genetic counsellors can advise/educate other clinicians who aren’t specialized in the area on how to introduce patients to genetics and order tests. The benefits of mainstreaming include reduced cost, wait times and maximising efficiency so that the right tests can be ordered for patients in a timely manner.

For more information on genetic counsellors and how they come into play in the context of cancer, check out the resources below.

“Quick Reference Guide” Handout

This resource was designed to help guide patients through conversations with their doctor or genetic counsellor about genetic testing; it includes questions to ask and terms to know.

Genetic Counseling For Hereditary Cancer Risk

This resource gives a detailed description of the role of a genetic counsellor, including what they do before and after genetic testing and the main topics covered during appointments.

Hereditary Cancer Patient Brochure

This brochure covers the process of accessing genetic testing for hereditary cancers, which cancers are currently tested for in the hereditary panels, genetic testing and the included services, as well as who tends to qualify for genetic testing.

“Genetic Testing: Your Questions Answered” Handout

This resource developed by the Canadian Association of Genetic Counsellors helps familiarize patients with some key terms when it comes to genetics including what are genes, hereditary cancers, genetic counsellors, genetic testing and its benefits, as well as what this means for insurance.

What to Expect During a Genetic Test

The following information was taken from the Canadian Urologist Association, Genetic Testing for Prostate Cancer

Dr. Richardo Rendon, MSc, Community Health & Epidemiology, PhD, FRCSC, Director of Research, Department of Urology, Dalhousie University

Dr. Michael Kolinsky, MD, PhD, Medical Oncologist at the Cross Cancer Institute, CCTG PR25 study chair

Dr. Shamini Selvarajah, PhD, DABMGG, FACMG, FCCMG, Assistant Professor, Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathobiology – Cytogenetics

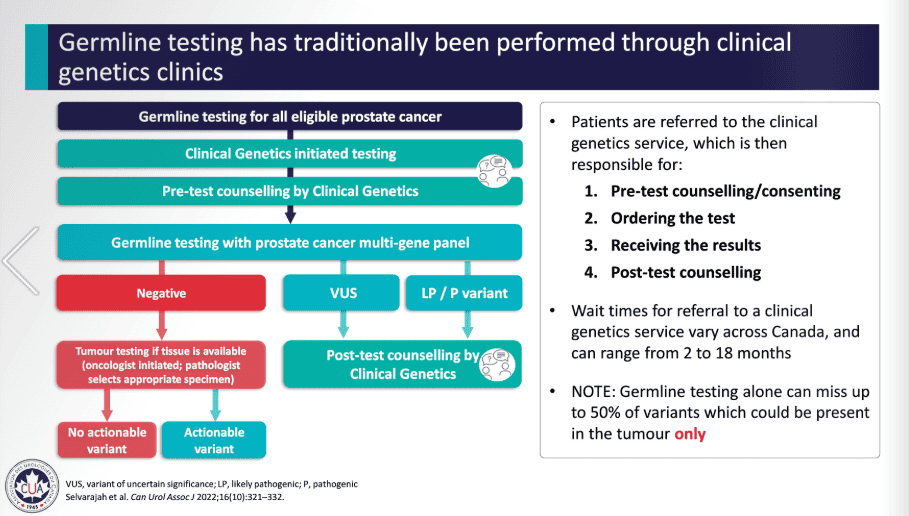

Hereditary Genetic Testing Process [7]

Below is a flowchart that gives an overall summary of the process for genetic testing, which can be done to detect both cancer that was developed throughout a person’s lifetime (acquired) or cancer that runs in the family (germline/hereditary). In this case, the germline testing process specifically is being outlined.

VUS: Variant of Unknown Significance, meaning more research is needed to confirm or deny whether this biomarker/gene is involved in cancer.

LP/P: Likely Pathogenic & Pathogenic variants, meaning biomarkers were found that are known to cause cancer, in this case prostate cancer.

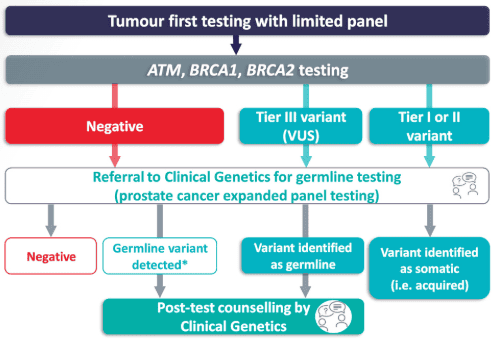

Tumour Testing Process [8]

Below is a similar flowchart outlining the process for tumour testing, also referred to as somatic testing; mutations discovered through this process haven’t necessarily been passed down from a person’s parents. To confirm whether or not this is the case, blood testing from a distant site should be performed to figure out which type of mutation it is (acquired or somatic).

VUS: Variant of Unknown Significance, meaning more research is needed to confirm or deny whether this biomarker/gene is involved in cancer.

Additional Resources

“About Genetic Testing” Handout

This handout explains what genetic testing is, what type of healthcare professionals assist in the process, and what testing might look like for a person with cancer vs for their family members.

“What are the Risks with BRCA Mutation” Handout

If a biomarker known to be associated with a certain cancer type is discovered during a genetic test, there are varying levels of cancer risk depending on the identity of the biomarker. The different levels of risk tied to each are outlined in this handout.

What Do Your Genetic Test Results Mean?

This resource summarizes the key information you should know to understand your genetic test results once they come back from the lab.

Sporadic vs Hereditary Cancer Info Sheet

This resource compares hereditary vs non-hereditary or sporadic cancer. It also explains what a positive, true negative, uninformative negative and “variant of unknown significance” result means for a patient.

Hereditary Cancer Genetic Testing – Mainstreaming – Youtube video

A video that explains hereditary cancer overall, what genetic testing is, how it can help you and your family, and other related information.

“What do your genetic test results mean” handout

This resource lists the three possible types of genetic test results and goes into detail about what each of them mean.

Genetic Testing Resources | Basser Center

At this link you can find videos about genetic testing developed as pre-test education in an effort to increase patient awareness of their options and in turn testing rates for those with prostate and pancreatic cancer. Scroll down to see a chart with biomarkers (genes) and their associated syndromes + cancers.

Making Sense of Genetic Test Results for Hereditary Cancer

This Youtube video created by a board certified genetic counsellor explains possible genetic test results in detail, what they mean for the patient, and what they saw in the lab to come up with that result.

Introduction to Hereditary Cancer

The attached Youtube video made by a board certified genetic counsellor introduces the topic of hereditary cancers, the role of a genetic counsellor, how family history comes into play, insurance discrimination, and other related information.

Youtube video about hereditary cancer and genetic testing

This video describes hereditary cancer in general and how genetic tests can help identify these.

Impact of CGP on Treatment

As mentioned above, once genetic test or CGP results come back for someone with cancer, this information can allow clinicians to tailor treatment decisions more specifically to that patient based on their identified biomarker. This process of coupling a test result to a precision medicine therapy is called companion diagnostics.

A common treatment that has been specifically designed to target a biomarker would be PARP inhibitors (i.e. Lynparza[9] and Zejula[10]), which are used on patients whose test results indicate a mutation in their BRCA gene[11]. This would be mainly people with breast, ovarian and prostate cancer[12].

Click here for a list of precision medicine therapies approved in Canada from 2018 onwards.[13]

CITATIONS

[1] Comprehensive genomic profiling. Roche Sequencing . (n.d.). https://sequencing.roche.com/global/en/article-listing/comprehensive-genomic-profiling.html#:~:text=CGP%20can%20provide%20more%20valuable,receive%20better%20targeted%20personalized%20treatment.

[2] Genetic tests available. CHEO. (n.d.). https://www.cheo.on.ca/en/clinics-services-programs/genetic-tests-available.aspx

[3] Middleton, A., Taverner, N., Moreton, N. et al. (2023). The genetic counsellor role in the United Kingdom. Eur J Hum Genet 31, 13–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01212-9

[4] Middleton, A., Taverner, N., Moreton, N. et al. (2023). The genetic counsellor role in the United Kingdom. Eur J Hum Genet 31, 13–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01212-9

[5] Middleton, A., Taverner, N., Moreton, N. et al. (2023). The genetic counsellor role in the United Kingdom. Eur J Hum Genet 31, 13–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01212-9

[6] Middleton, A., Taverner, N., Moreton, N. et al. (2023). The genetic counsellor role in the United Kingdom. Eur J Hum Genet 31, 13–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-022-01212-9

[7] Rendon, R., Kolinsky , M., & Selvarajah, S. (2023, April 26). Genetic Testing for Prostate Cancer . Canadian Urological Association. https://www.cua.org/program/16882

[8] Rendon, R., Kolinsky , M., & Selvarajah, S. (2023, April 26). Genetic Testing for Prostate Cancer . Canadian Urological Association. https://www.cua.org/program/16882

[9] AstraZeneca Canada Inc. (2025). Olaparib [Drug information]. Retrieved August 25, 2025, from https://www.astrazeneca.ca/content/dam/az-ca/downloads/productinformation/lynparza-product-monograph-en.pdf

[10] GlaxoSmithKline Inc. (2023). Niraparib [Drug information]. Retrieved August 25, 2025, from https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00072135.PDF

[11] Fadi Taza et al. Differential Activity of PARP Inhibitors in BRCA1– Versus BRCA2-Altered Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 5, 1200-1220(2021).

[12] Fadi Taza et al. Differential Activity of PARP Inhibitors in BRCA1– Versus BRCA2-Altered Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 5, 1200-1220(2021).

[13] Government of Canada. (2025, April 9). https://www.canada.ca/en/patented-medicine-prices-review/services/hearings/decisions-and-orders.html